Elena Vavassori is an Anaesthetist-Rianimist at the Fondazione Poliambulanza Istituto Ospedaliero di Brescia. For a number of years she has been involved in narrative medicine and has recently taken an interest in traditional Chinese medicine, in a combination of knowledge and interests always in search of contact with the human.

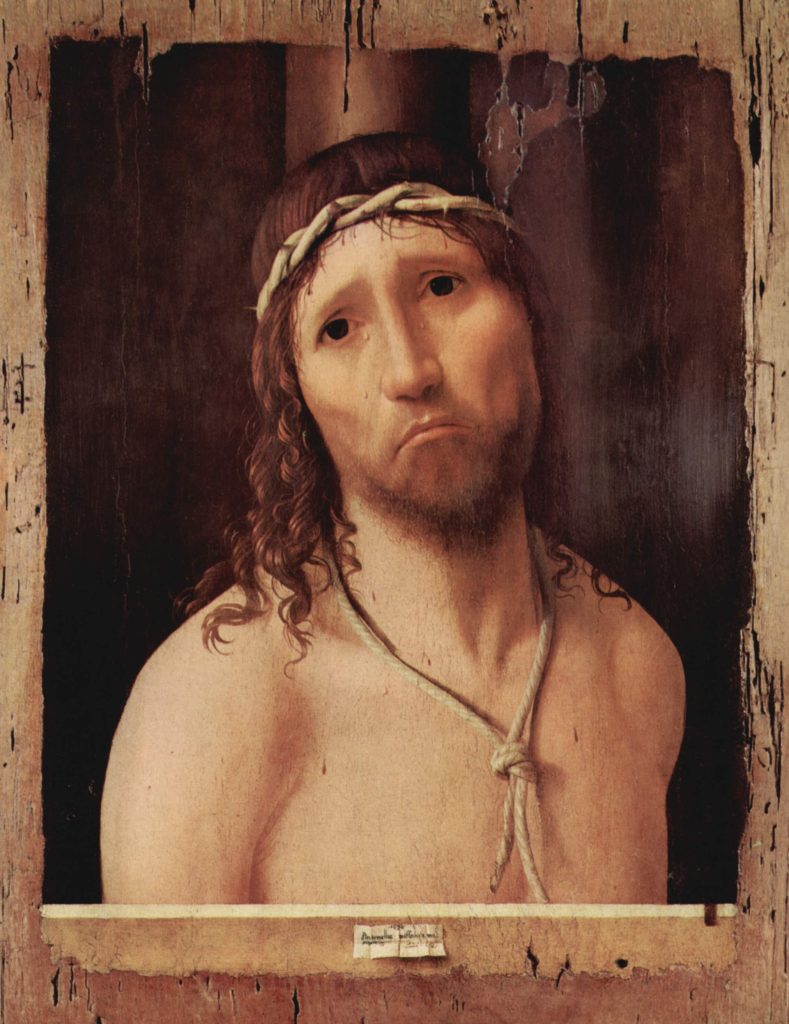

The pictorial image that comes to mind when thinking about fragility, and the fragility of man, is the Ecce Homo (1475) by Antonello da Messina, which I saw a few years ago and still remember with the same emotion. Looking at that face and gaze, the face and gaze of Christ, what moved me most were the tears that make the divine human. The face of a man like us who are looking at him and with whom we can share our tears without shame.

And it is from a story of tears that the idea was born to collect the narratives of anaesthesiologist colleagues in the time of Covid, when the pandemic swept over all existence and when every moment was every day and at the same time a single day, a single plot. During the morning briefing in the ICU, some colleagues wept as they recounted the deaths occurred during the night. In recounting the lives that were not saved, of those who left without being able to have anyone near them but those who were already busy rescuing someone else who arrived.

In their stories, the metaphorical language allowed them to say all the complexity of the moment they had lived through:

- Now I feel in a state of war.

- Leaf of a tree on a windy autumn day.

- Don Quixote de la Mancha fighting against the windmills.

- On everyone’s face there was a veil, a blanket, and everyone seemed locked in their own despair.

Let us not forget that all this was part of everyone’s personal history and the reasons why they had chosen to be a doctor. But also of what the doctor represented in their eyes, the figure of the doctor who overcame years of study and sacrifice to enter what was believed to be a circle of the elect.

Being a doctor in Covid’s time certainly meant coming to terms with one’s passion, and then more than ever inextricably linked to uncertainty, fear, feeling fragile, discovering the limits of one’s knowledge. Tears found their sense and value from not emerging victorious in the struggle between life and death. Tears are the expression of a vulnerability that can no longer be held back (we know, doctors do not cry).

Our culture regulates who can cry (females) but also where, how and when to cry. In my opinion this taboo was broken and overcome in the time of the Covid: almost as if tears were the only language able to connect those who where still here and who were gone, the world of the living from that of the dead, in the common pain of loss. One might even think that in those briefings, tears represented the sound of grief and at the same time a new, stronger and no longer forgettable knowledge.

Then under the goodness of the heavens/

I am as naked as when I was born/Behind the thin veil of tears/

Then I am only me.

But in that dark moment, when the landscape in which to live one’s profession had changed, one went in search of a light. And here other metaphors gave voice to the feeling of the medical resuscitators:

- No tear has not been wiped away, and this warms the heart and allows you to hope for the future.

- I felt like one of the hundreds of rowers on an ancient ship.

The first time that, after a night shift and after talking on the phone with relatives of people admitted to intensive care, I saw a banner hanging on the hospital’s outer gate saying: ‘Thank you for what you do, you are heroes’, I did not hold back my tears, thinking that just before I had said words that shattered the hope that a life could go on.

So who is the hero? ‘Heroes are all young and beautiful’, Guccini sang. And do we understand fragility as imperfection and defeat? Or as a choice to inhabit and live the limit so that it can be transformed into resilience and, why not, creativity? Thus pushing our gaze from paralysing emotion and weeping towards a hitherto unknown horizon. The world of fragility as a world of resources, with the possibility of further openings. Can this be the new hero? The one who knows and can weep without shame, the one who is a man and, as in the painting of Ecce Homo, does not look to Heaven seeking answers or pity for his fate, but welcomes and passes through the trial he did not choose but to which he was called, and looks at us with a sorrowful gaze, seeking in us a new light, even for ourselves.

On the other hand, I find the figure of the hero that inhabits our culture and imagination risky in healthcare, but also in life: the one who always offers us salvation, intolerant of rules and unaware of limits and risk, projected towards a world where there are only certainties and not anguish, embodying expectations and promises that he cannot keep because he is not master of either time or his own destiny, let alone the time and destiny of others. In fact, we all know of complaints suffered by doctors defined as heroes because, precisely, they are invested with that myth of the hero as a perfect being, untouchable and unbeatable in the face of adversity. The figure of the hero thus understood does not, I think, benefit health workers, just as I am not convinced by the talks with the psychologist to deal with the anxiety and stress that the Covid time has generated in many of us.

Instead, I believe more and more in training that brings into everyday life the language of emotions. In my reality I experience this every time I present and read narratives of suffering people or their relatives, because transforming a destiny (such as that of illness) into a recounted experience unites everyone’s destinies and this makes suffering comprehensible in an immediate way. And this is where remedies can start. Recently, when presenting narratives on chronic pain, I started by reading what I called a declaration of love by a wife to her sick husband:

- I love my husband, I also love his sickness, I have always thought that love is an all-powerful feeling, capable of overcoming any obstacle. I am convinced of this, but this does not detract from the fact that loving without limits and boundaries is the most complex thing one can experience in life.

This aroused emotion and, finally, a few tears in the listener. And so, without shame, how to transform this love, this feeling that the doctor reads so told in a story not written by him in the classic anamnesis, and how to insert it into the care path of that family? By accepting and protecting this woman’s voice by recognising the value of truth. And in so doing accepting the precious good of one’s own and others’ fragility understood as sensitivity, tenderness, dignity, and as a constitutive and structural element of the care relationship and not extraneous to it. This makes us all stronger, and even a little heroic.