In Francis Bacon‘s New Atlantis, Tommaso Campanella‘s City of the Sun and Thomas More‘s island of Utopia, there are rules for creating wellbeing in society: education (including women, and we are in the 15th-16th-17th centuries), fair distribution of possessions, production for consumption and not for enrichment, and knowledge of various languages, even the ancient ones. In the New Atlantis, Bacon dwells on the need for scientific experimentation on dead bodies, plants and the preservation of organs to create knowledge and well-being.

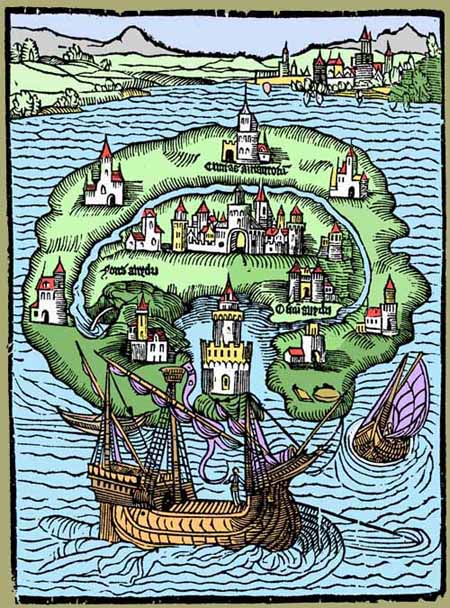

The City of the Sun (perhaps Sri Lanka), and the New Atlantis, discovered by serendipity after a shipwreck in the South Seas, are utopian cities, geographically located far away, on separate islands, difficult to reach. More’s Island of U-topia (from ou-topos, no place, or perhaps eu-topos, a good place) is also located in an elsewhere that is difficult to define: insularity means isolation from the earthly and corrupt world, distance and remoteness, if not inaccessibility. In these islands or cities, all the people are happy, and the goal of the governors is the population happiness. That is possible because no one has more than others: envy, one of the capital vices, which arises precisely from not having the stuff of others, cannot germinate.

Campanella writes: “I was born to eradicate three extreme evils: / tyranny, sophistry, hypocrisy; […] / Famines, wars, plagues, envy, deceit, / injustice, lust, sloth, disdain, / all of which are subject to those three great evils, / which have their root and foment in blind self-love, worthy son / of ignorance”. Plague and famine are dependent on human behaviour such as tyranny – totalitarian and absolutist government, sophistry – rhetoric for its own sake aimed at personal advantage, and hypocrisy (which can be understood as current denialism) – denying meaning to the things that happen, to nature with its phenomena and excesses.

The philosopher scientists More, Bacon and Campanella, with their heretic and “illegal” political thoughts, spent part of their lives in prison: Thomas More was even beheaded for not having signed in favour of Henry VIII. It is plausible, therefore, that they dreamt of better, fairer worlds, where culture was seen as a common good and not as some form of power to manage the crowds, who had to remain in ignorance and, in extreme cases, in misery.

Utopia is opposed to Dystopia (dys, bad and topos, place), the representation of an imaginary reality of the future, predictable on the basis of highly negative trends of the present, in which an undesirable or frightening life is foreshadowed. The society is characterised by oppressive social or political phenomena, in conjunction with or as a consequence of dangerous environmental or technological conditions, including post atomic world wars, meteorites, glaciation, pandemics. The term dystopian originated, ironically, from a speech by the liberal economist Stuart Mill to recall the lack of freedom of movement, trade, and enrichment. An origin, then, far from the one of utopia. The dystopian genre was successful in the last century because its imagery originated from a twofold trauma: on one hand, the shock produced by the acceleration of technical and scientific progress, which lead to dehumanisation and alienation, or the destruction of the environment and humanity itself; on the other hand, the trauma caused in the first half of the 20th century by the rising of totalitarian regimes such as the Fascist, Nazi and Stalinist regimes, which largely inspired dystopian literature.

Among the great exponents is Aldous Huxley, author of Brave New World (1932), which describes a world based on eugenics and castes. The alpha caste consists of individuals destined for leadership, the betas hold administrative positions requiring higher education, but without the responsibilities of command. The gammas are created and trained to take on the most menial jobs and in the harshest conditions without complaint. Delta children are conditioned through electric shocks to be afraid of flowers and books in order to take on the most menial tasks; epsilons, conditioned from childhood to hate nature and the countryside and to love cities and factories, take on the ugliest jobs and under the harshest conditions. In general, all individuals are mentally conditioned to conform to the role they will play in society.

Another exponent of the dystopic genre is George Orwell. Quotations from his book 1984 were favourites of people who were opposed to the Covid-19 pandemic lock down and to the continuous laws that restricted people’s movement. In George Orwell’s book 1984, we follow the main protagonist Winston Smith as he navigates London in what he believes to be the year 1984. Working for the Ministry of Truth, he spends his days as a journalist altering news articles and erasing the past. This is the world he lives in. A world in which the past, present and future are managed by Big Brother and members of the Ingsoc Inner Party, the governing ideology of the Oceania region. In Oceania, privacy does not exist. Secret telescreens and microphones are everywhere: in the streets, workplaces, restaurants and especially in homes: they watch you and listen to you. All that is private is your thoughts, and even those are illegal if they don’t obey Ingsoc’s beliefs. It’s called Thoughtcrime. Thoughtcrime describes a person’s politically unorthodox thoughts, such as beliefs and doubts that contradict Ingsoc’s principles.

In a online post, the author – clearly against lockdowns and forced restriction of personal freedom – states that: “2020 has seen a wave of pulling wrong thoughts from the minds of others. Articles and social media posts that don’t align with the story we are fed are quickly censored and taken down under the context that spreading false information is a major safety concern for the health and well-being of our society during a time of crisis.[…] [People] are losing their jobs and careers, and their reputations are being tarnished as a result of cancel culture and essentially 1984’s thoughtcrime.” There are many others post similar to this one on the net: just type ‘Orwell and pandemic’ into Google and anything comes up. Without taking any position on the matter, it is true that many have lost their jobs and careers, it is true that vaccination was not only given to the most fragile in the beginning, it is true that the Green Pass and Covid Free islands will create another dystopian narrative.

And so it reminds me of two dystopian science fiction movies released before the “dystopian film” of the pandemic that we have been living on our skin and within our skin since 21 February 2020. These are films that are not about viral contagions or stories that want to set themselves up as prophetic of viruses that have escaped from the Wuhan labs. Elyseum and Snowpiercer are two names that inhabit my head, like two possible readings of what is happening, not only in our little old world “Europe”, which is not very capable of signing proper contracts with some pharmaceutical companies to get vaccines, but also in other countries and continents, where we are already counting the deaths due to lack of access to treatment, respirators, oxygen, and finally the vaccine.

Elyseum is a 2013 film starring Jodie Foster and Matt Dammon directed by the South African Canadian Neil Blomkamp. In 2154 mankind is divided into two castes: a select few, the rich, live on an enormous space station called Elysium, orbiting around the Earth, luxurious, futuristic and equipped with a perfect terrestrial ecosystem; and the poor, the vast majority, live on planet Earth, now overpopulated, extremely polluted and almost uninhabitable because of the state of great decay. The government of Elysium establishes stricter and stricter laws against immigration, in order to preserve the luxury and well-being of the privileged few who live there, and to stop by shooting down with missiles the unauthorised ships the people who, from Earth, continually try to reach the station as illegal immigrants. A worker on Earth, Max (Matt Dammon), is exposed to a huge dose of gamma radiation, which, according to the medical robots serving the poor inhabitants of Earth, will kill him within five days. Max’s only remaining hope is to reach quickly Elysium, where he can use the highly advanced medical capsules, which can heal any illness or physical damage in seconds, even very serious ones. He will find as his antagonist Jodie Foster, chief of police of Elysium. I will not tell the sequel for the reader, but it is clear that the whole film is about the accessibility of technologically advanced treatments.

The other, Snowpiercer, is a 2013 film directed by Bong Joon-ho (also director of Parasite), based on the graphic novel Le Transperceneige, a post-apocalyptic science fiction comic. The year is 2031. In a world decimated by a new ice age, caused by failed experiments to stop global warming, a group of 2100 people remain alive inside a train, the “Snowpiercer”, which continues to move around the Earth and obtains the necessary energy through a perpetual engine. The train is a microcosm of human society divided into social classes: the poorest live crammed into the last carriages, where they feed exclusively on protein bars made from insects; the richest live in the front carriages. Informed of how the upper classes live by people in prison at the back of the train, the nobodies start the revolution. The theme of food, care and available space is the leitmotif of the film. Interestingly, the original thinking (the earth is slowly recovering and becoming habitable again) is in the wagon of the desperate, while the wealthy classes – in truth, many of them are the economic investors in the train – and their children continue to believe, Big Brother style, in the sophistry that the train is the best of all possible worlds.

Back to the 2020-2021 pandemic: the report by Michael Marmot, Professor of Epidemiology at University College of London and Director of the Institution of Health Equity, which came out in December 2020 and concerned the UK and may be paradigmatic for other countries, had as its title, Build Back Fairer. Again in an April 2021 interview in The Guardian, Malmot confirms that the pandemic and the associated social response have amplified social and economic inequalities from early childhood, education, employment, having enough money to live on, housing and community. It also showed even steeper social gradients in mortality rates and surprisingly high mortality rates among people from ethnic minorities. Much of this excess can be attributed to poverty or lack of access to care.

The whole year of the Covid experience has been immense to bear not only for our bodies, but also for our minds and souls, in terms of access to care: from the availability of oxygen, masks, personal protective equipment, available beds, to the current case of vaccination, which is extremely delayed in Italy – one of the five countries in the world most affected by the pandemic. Now the Green Pass – which states that only vaccinated people or people who have had the Covid will be able to move – puts us in a condition similar to a dystopian place (discrimination). Already, scientists are objecting, given the uncertainty, to giving the green light for travel to people who are negative for a swab taken two days earlier.

The vaccination calendar, with the exception of health professionals, has been full of iniquities: only at the end of March, after vaccinating professors, some judges and administrative staff in the public administration, they begun to vaccinate the fragile population over 80 and younger people in vulnerable situations. Now millions of people in Italy are still waiting for the first injection of vaccine and, in the meantime, the government, in order to boost tourism, is creating Covid-free islands like Capri, Panarea, places for very rich people: vaccines will be given more slowly to the “normal population” but faster to recreate this kind of paradise.

The younger generation is paying an undignified price because it will be the last to receive the vaccine, so it seriously risks not finding jobs or not being able to travel and learn more. About the islands, the Covid Free slogan has been created to boost tourism: on islands such as the Aeolian Islands or Capri the entire population will be vaccinated, regardless of the objective risk of vulnerability: holidays on the island will be utopian for those who bought them through monetary wealth; and idea far away from the utopian islands described by the three Bacon, Campanella and More. On the other end, unvaccinated people still pay and will pay a price in freedom of movement and opportunities, young people especially, with fewer chances for employment because they are not yet vaccinated, in a society that is even more dystopian for them. The Green Pass will have to be implemented when the majority of the population is equally vaccinated. Without considering for now the sensible or senseless hypothesis of herd immunity.