PROJECT WORK WITHIN THE MASTER OF NARRATIVE MEDICINE

Authors

– Dr. Luca Fontanini: physiotherapist, kinesiologist and philosopher at FISIOALFA®, president of the cultural association Ritorno all’Essere Umani®.

– Dr. Emanuela Sozio: hospital doctor at Azienda Sanitaria Friuli Centrale, vice-president of the cultural association Ritorno all’Essere Umani®.

– Dr. Giuliana Balzano: nurse, writer, editor and director of the ‘Storia di Vita’ series for the Leucotea Publishing House.

Objectives

The aim of this work is to investigate in a transversal manner reflection on the theme of death. Questioning oneself about living with the thought of the end of life on a daily basis can help to juggle the paradox that includes not giving in to illness and the difficult acceptance of the inevitability of death. Reversing perspectives through specific reflections can dampen the gloominess characteristic of this delicate topic and can give the time of existence the quality it deserves, a quality also based on the caring relationship. Reflecting in these terms is a valuable meditation on life and can both offer meaning to a shared experience and create a connection with the Other. We involved in this study both citizens and health professionals who are at the service of people in the most delicate and crucial moments of their existence. Understanding, therefore, what are the points of contact between health professionals and non-health professionals on this issue, is the first step in enriching the care process and is also our goal.

The narrative evidence

We asked the people participating in the study to share, totally anonymously, some reflections on the subject of death, inviting them to freely write thoughts and stories from ten semi-structured tracks consisting of sentences, photographs, a haiku and a short film. A total of 110 people agreed to participate in this project: 46 of these (or 42%) are health professionals and 64 of these (or 58%) are citizens who are not in a care profession. The average age of the participants is 48 years ± 13 years.

Below are three of the narrative prompts used and considered most significant:

– ‘If I became aware of my “due date”…’. From the narratives received, it appears that for most people this could turn out to be a positive piece of information, as it would function as a driving force to change their attitude towards life. The hypothetical announced date, therefore, would change the trajectory of existence both in terms of doing and being. Many people would endeavour not to waste their remaining time, trying to fulfil dreams or travel, and would stay closer to their loved ones, giving love and trying to receive it; however, it seems that death is a foreign and distant event for them. It seems, therefore, that it is necessary to know one’s ‘expiration date’ in order to start spending one’s energies on situations and events of real interest, instead of living intensely by loving and being loved regardless. We have noticed, analysing the narratives, that the health professionals, being more in contact with suffering, illness and death, have a particular focus on the subject of ‘finite life’ and speak about it with a certain ease, more openly, and this is perhaps the most tangible difference between the two groups: it is not so much the content but the way of writing and expressing these concepts.

– ‘After my death I would like something to remain of me…’. Almost all people wish to leave something of them, a memory or personal characteristics and qualities, such as a smile, a laugh, a thought. On the one hand, death is imagined as a subjective experience, but on the other hand, the need – inherent in human nature – not to leave and to remain in and through Others is manifested. Within some narratives in particular, the semantic area of the good and the beautiful are recurrent. Both emphasise – in an almost narcissistic manner – every aspect that should be remembered and kept alive in those who remain, taking it for granted that it is valuable and deserving to remain imprinted. The narratives, on the whole, emphasise both the desire to remain in memory (memorial approach) and to leave something that can continue to exist (generative approach). For the human being, therefore, leaving something behind is a state of necessity.

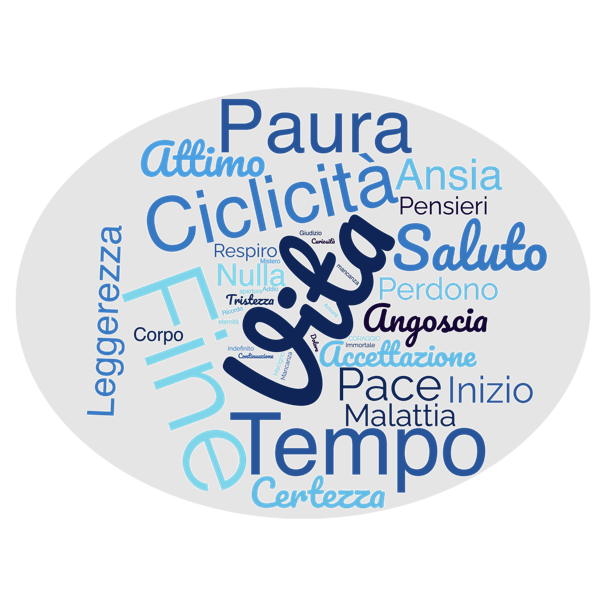

– ‘Choose three words to associate with death’. From a shortlist of 20 words, the 110 participants in the study indicated the following, proposed here in descending order according to frequency of selection: life 41 (38%), end 30 (27%), peace 23 (21%), time 23 (21%), cyclicality 23 (21%), acceptance 22 (20%), fear 21 (18%), certainty 16 (14%), goodbye 16 (14%), anguish 15 (14%), forgiveness 14 (13%), anxiety 11 (10%), illness 11 (10%), beginning 11 (10%), lightness 10 (9%), moment 9 (8%), body 8 (8%), breath 7 (6.3%), nothing 6 (5%), thoughts 4 (6%), sadness 2 (2%), lack 2 (2%). The choice made by health professionals compared to that made by non-health professionals shows some differences (Figures 1 and 2): in the group of health professionals there is a greater tendency to use the words certainty, cyclicity, acceptance, illness, body, breath; in the group of non-health professionals there is a greater tendency to use the words end, forgiveness, anguish, moment. In contrast, the words life, time, greeting, fear, beginning, anxiety, lightness are used equally by the two groups. Carrying out a caring profession inevitably confronts people with corporeity, illness and the cyclical inevitability of death, which also involves accepting it; those who do not experience death through work, on the other hand, experience it with greater anxiety and only recognise its final phase, which can be traced back, temporally speaking, to a ‘moment’.

Figure 1. Cloud of words used by healthcare professionals.

Figure 2. Cloud of words used by non-health professionals.

And what to do with it …

In conclusion, the difference between the group of health workers and the group of non-health workers appears blurred, except for some word choices and narrative tones. The subjective characteristics of each response, if we look at them from an overall and multi-layered perspective, unite the various professions, and highlight the same ontological basis of human beings, who are similar in terms of being, before and regardless of the type of their doing.

Finally, some questions of a philosophical nature come to mind, which we deliberately leave open: For what reasons of everyday life, of contingency, is the thought of little time emphasised especially in the proximity of inauspicious events? Why do we find ourselves disoriented before the certainty of our own death? Why is it more often death that makes one reflect on life, rather than being considered part of it?