The word theatre comes from the Latin theatrum, and this from the Greek ϑέατρον, which indicated the building for dramatic performances but also that for assemblies and political life. In fact, the Greek noun comes from ϑεάομαι ‘to watch, to be a spectator’. From the same root we also derive the verb θεωρεω, which has the meaning of observing, understanding, understanding, and from which we also unexpectedly get the word theory.

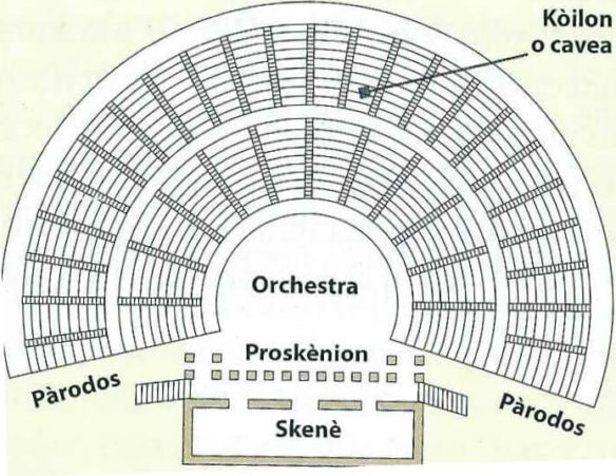

The ancient Greek theatre consisted of a sloping semicircle of tiers known as the cavea, in the centre of which was an open space, the orchestra, where the chorus danced and dialogued with the actors on stage (proskenion) through the figure of the coryphaeus (a kind of spokesman for the chorus). The whole community attended the performances, which are moments of democratic reflection on the great political, philosophical and existential themes of community life.

The main text analysing ancient theatre is Aristotle’s Poetics, in which the philosopher investigates the relationship of tragedy and epic (it is postulated that there was a second book entirely dedicated to comedy, but it is now lost – editor’s note: read The Name of the Rose) with the world (concept of mimesis) and with the spectator (concept of catársi). Mimesis consists in the imitation of the world’s most immediate mode, and becomes a transparent metaphor for it. Catharsis, on the other hand, is the spectator’s emotional involvement in the performance that allows the passions to be released.

Theatre is the realm of the ‘as if’ and so is play. The link between the two realms is most evident in the fact that the verb expressing the action of playing and acting is the same in many languages (to play, jouer, spielen, etc.). The game or acting can only be carried out if all participants adapt to the rules, precisely ‘of the game’. In both spheres, moreover, the body has a semantic, signifying function, even when a verbal framework is absent.

The theatrical metaphor allows one to experience the world without living it seriously, to experience a fiction as if it were reality, with body and mind. And herein lies, on the one hand, the therapeutic and gnoseological potential, of knowledge, of theatre. This, in fact, whether one practices it or witnesses it, allows one to see (and experience) emotions and facts from an external perspective, to strangle everyday phenomena and judge them in a new light.

Please leave us a word for your feeling of theatre.