Star light

I will be chasing a starlight.

Until the end of my life

I don’t know if it’s worth anymore…

My life

You electrify my life.

Let’s conspire to ignite

All the souls that would die just to feel alive

Luce stellare

Inseguirò la luce di una stella

Fino alla fine della mia vita

Non so se ne valga ancora la pena

La mia vita

Tu elettrizzi la mia vita

Cospiriamo per accendere

Tutte le anime che morirebbero solo per sentirsi vive

Muse

The art of healing

The benefits from art on health are so obvious that the World Health Organization (WHO) promoted the integration of art and medical care at its first dedicated congress in Finland in 2019. This was followed by the development of guidelines for the integration of art into the pathway of diagnosis, treatment and care.

These are the planned areas of action: helping people suffering from mental illness; intervening in illness resulting from trauma and abuse; supporting care for people in acute conditions, such as during hospitalization, including intensive care; supporting people with neurological disorders such as autism, cerebral palsy and stroke, degenerative neurological disorders, and dementia; and again, assisting in the treatment of cancer, lung disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease; and finally, supporting end-of-life care.

Even in an acute phase, destined to become a new daily routine, art, as per the evidence in the report (Health Evidence Network synthesis report: what is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being?) helps people not to think obsessively about what has happened and in a sense realize that life offers new possibilities for expression, despite everything. The creative process allows the processing and overcoming of an inner malaise, thus also improving the quality of human relationships.

The power of art in healing is institutionalized in the WHO report, and there are multiple neuroscientific evidences-ripened in the last two decades thanks to imaging-that prove the effects that artistic languages exert on the Sapiens- Neanderthal brain: this is not enough, a great fog dense with prejudices and utilitarianism wish to confine art in an “other” dimension, far from the paths of healing. Prejudices due to confining art to an “old-fashioned” dimension, as if it were part of a primitive folklore, devaluing even the wisdom of traditional knowledge, and utilitarianism due to the fact that there is not much investment behind proving that art is therapeutic: the world of pharmaceutical and biomedical companies generally funds controlled studies to prove the efficacy of drugs and medical devices, and spontaneous research is rare.

The purpose of this book is to collect-for different forms of art and beauty-the meaning, history, traditions, and transformative moment in the transition from art to art therapy and who the initiators were. Quantum leap is precisely this shift from art to art therapy, which occurred in the last century: some artists who were often also pioneering clinicians began to gather evidence of how art worked on human beings through quantitative interviews and questionnaires. It was the advent of imaging that allowed a further evolutionary leap, the understanding of what happens inside our bodies during immersion in art. This book is a valuable treasure chest for skeptics to begin to read that in some good healing practices, music, aromas, painting, poetry, books, writing, films, colors, sounds, songs, dance, theater, sculpture are “prescribed.” These are the art languages we call Muses: some are primal, colors and aromas, which go back to our history as hunter gatherers, sculpture in the way of shaping the first objects with mud, painting, whose earliest representations are in the sanctuaries of the Lascaux or Altamura caves, and the poetic songs that Bruce Chatwin tells us about in “The Ways of Songs” at the nomadic Aboriginal people in Australia.

A probable historical demarcation exists with the invention of writing and the written word-where the symbol replaces the image, and finally with the cinema, which may take up the game our ancestors played with the shadows cast by fire inside enclosed places, caves, caverns or huts that they were. As if to say that these arts are lost in the mists of time, languages connoted with our perceptive and creative capacity and entered into our collective unconscious and acquired DNA.

Why do we call these arts the new Muses? In the classical tradition they were nine sisters, daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (the “Memory”) and represented the supreme ideal of art, understood as the truth of the “All” or the “eternal magnificence of the divine.” Walter Friedrich Otto traces their characteristics: “The Muses have a very high, indeed unique, place in the divine hierarchy. They are called daughters of Zeus, born of Mnemosyne, the Goddess of memory; but this is not all, for they, and they alone, are reserved to bear, like the very father of the Gods, the appellation of Olympians, an appellation with which they used to honor the Gods in general, but-at least originally-no Gods in particular, with the exception of Zeus and the Muses.” They were thus gods, fundamental this inspiring thought. And where did we place them? With what other deities have we replaced the arts? Plutocracy, greed, efficiencyism, power, technocracy, frontiers?

The exercise of going to the roots of words with etymology is revealing of the broader meanings of them: the word was sacred as the Muses, the word was God (in the beginning was the Word, and the Word was God and the Word was with God). Knowing that Aroma means an ‘invisible air or light, that music was an act of the Muses, whatever form it took-theater, dance or history or astronomy (for among the ancient Muses was Ourania muse of astronomy and geometry and Clio, muse of history): music went beyond, it was even before the Word, thus, even before God.

Reading “writing and sculpting” we hear inside our ears the strokes of the chisel to leave the first marks on the stone, whether it is about a text of symbols like the Rosetta Stone or about wanting to pull out of the inert marble the head of Medusa with its snake-like hair.

The Ta tan rhythm of the word Dance evokes to us the drums and the stretches, swings and bends of muscles, to free the body and to coordinate it with other human beings carrying out the same steps, creating a thread, in an ancient choreography (writing of dance, in Greek choreia means dance, and the chorai, the young girls, led it).

What about that caring, which has meant since the time of our ancestors, watching and observing? To care means to be focused with a wide gaze, so that other people can feel less pain of whatever nature it is, to develop more creativity and anti-fragility, a concept that surpasses that of resilience, the going back to square one with respect to impact, but evolving instead with respect to trauma.

We are living in dark times, there have always been wars (as a child I lived in the US-USSR Cold War era) but since Generation Y and Z have been in the world, never before have we had so much war on the doorstep: perhaps even the arts are an attempt to release the emotions one feels, to find in this rainy, warlike autumn of 2023, some rays of sunshine–of starlight as the Muses write and sing–and peace, between the rain that makes man-made rivers overflow and the violence generated by the war economy.

Art art therapy need not necessarily adhere to the classical canons of harmony, the code of golden proportions of Lysippus’ sculptures, Botticelli’s Venus, or Mozart’s music, or triumphant hymns in this present context; perhaps it is the asymmetries, the reds and blacks that need to come out on the canvas, the intimate music, like Arvo Part’s Spiegel im Spiegel (mirror in the mirror, an infinite reflection), the books without the happy ending, to take cognizance of how this Historia goes. Already taking cognizance is a happy ending, it is therapeutic, unveiling the truth produces maturity and planning to correct, remedy, heal.

Two suggestions

Let’s start reading this book written by 48 scientists by starting from the last paragraph of their chapters: Practice of… These are beads of art that each person can make on his or her own, at very little cost, nowadays said to be sustainable, that can release well-being, not only with each other but also with ourselves: sometimes we neglect ourselves too much to make room for our duties, commitments and others and we no longer know the art of stopping.

The second suggestion is about the evidence that art works to create health: this book is a vast search of evidence ranging from neuroscience to early studies to measure the effect of art. So it not only wishes to be manual but to provide evidence of the benefits of art to “skeptics.” If studies on the therapeutic arts do not include large numbers of sick people, let us also speculate why: economic investment to test yet another anti-inflammatory is favored as scientific dogma. Ironically, those few studies that have been done indicate to us that artistic enjoyment dramatically reduces the consumption of anti-inflammatories and painkillers.

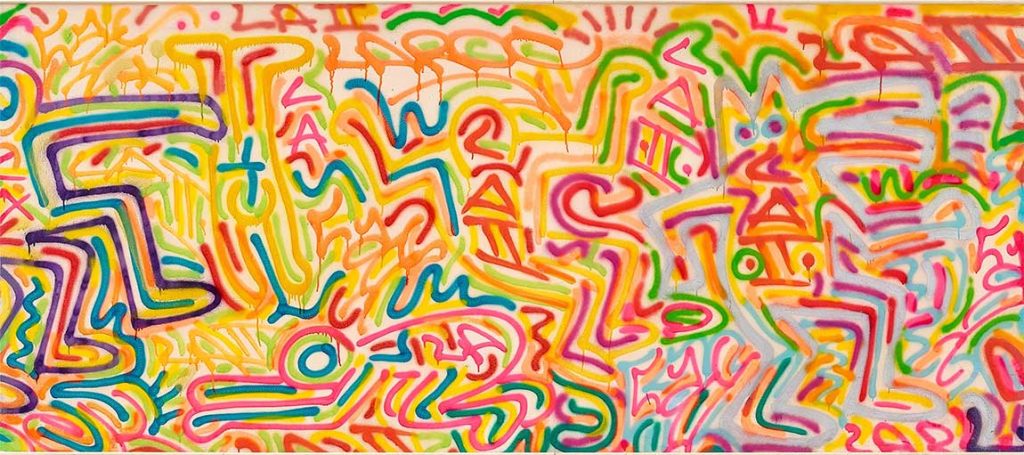

We therefore make a plea that investments in art are not only the work of collectors who can afford the originals of canvases at Sotheby’s auctions, but that Art Foundations together with Scientific Foundations can pursue this research in the other world of art therapies. Perhaps the same people at Sotheby’s who are now supporting Banksy and Keith Haring’s “Love in Paradise” exhibition will be able to fund the larger studies of the efficacy of the arts in treatment.