Giving voice to the testimonies of health care professionals in Italy between December 2023 and January 2024 was the goal of Istud research aimed at capturing health care motivations, energies, needs and behaviors: 176 narrators and storytellers left their written mark on the narrative invitations “I feel” … “I think…” “I want…”, “With others…” “With patients…” And this is the narrative method, the quintessential tool to give meaning to what happens inside health care organizations. But narrative goes deeper than the tests usually used to assess a phenomenon. Quantitative tests, which can be disconfirmed or logically related to the collected texts. In fact, the research “Life Inside Health Care Organizations” was based on mixed narrative and quantitative methods: on the one hand “small narrative fragments” on narrative invitation to the universal words “I feel”… “I think”… “I want”… “With others”…, “With patients…” on the other hand the burn-out test prepared by Cristina Maslach back in 1981, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, and designed for health care workers. How do caregivers operate and especially are they able to give Common Good?

That the word burn-out has become a negative mantra in health care in 2024, after Covid-19, due to further cuts in professional resources and financial issues, is taken for granted: yet we need to investigate whether the Burn Out test, which is based on three main domains such as Depersonalization (D, i.e., detachment from the patient in care, coldness, alienation, lack of empathy), Emotional Exhaustion (being exhausted by both emotional and workloads), and Personal Achievement (R, gratification, recognition, being able to make decisions independently) is so detective of the state of the National Health Service.

The socio-demographic results

A total of 176 people participated in the research, with an average age of 52 years: the figure is consistent with the ISTAT figure for collaborators in public administration, 51.8 years (this means the research reached the desired target), with an age range from 25 years of newly graduated physicians now in specialty to 77 years of those still working within the health service.

With the same stratification of contacts sent in the different regions, and asking for the research to be sent also to colleague people who had never done training on “soft skills- communication, storytelling,” the North responded with 65.9 percent perhaps demonstrating that participatory activism that wants to shed light on the situation in order to interject, the Center at 19.1 percent and the South at 15.8 percent. It should be noted, however, that the first region in terms of responses was Lombardy, second Piedmont, third Sicily, fourth Lazio, with Tuscany and Veneto. 73.9% of narrative and quantitative responses came from women, 25.5% from men, 0.6% write other. Data from the WHO 2019, indicate that in Italy 70 percent of the caring professions are performed by women, and in this sense, albeit with a slightly higher percentage, the research is aligned with this figure.

For the health professions, 44.4 percent are medics, 43.3 percent are nurses, and the remaining 12.3 percent are psychologists, physiotherapsists, logopedists, and others working in health care.

Maslach’s test results

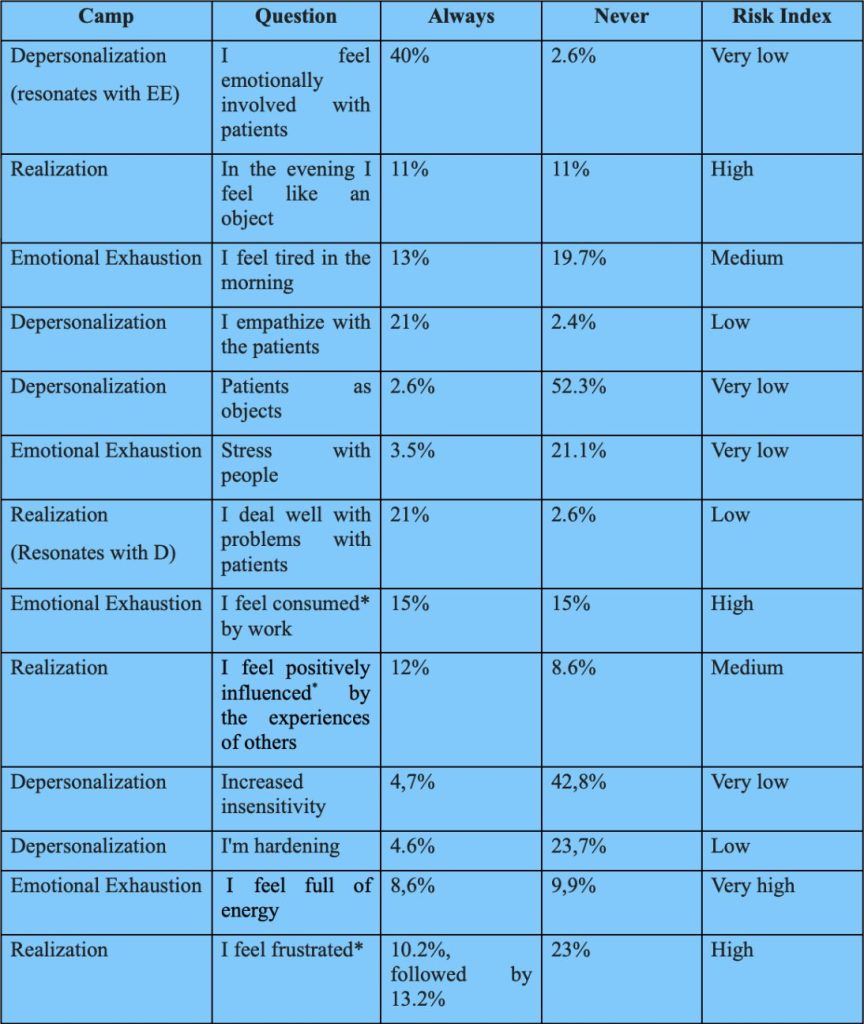

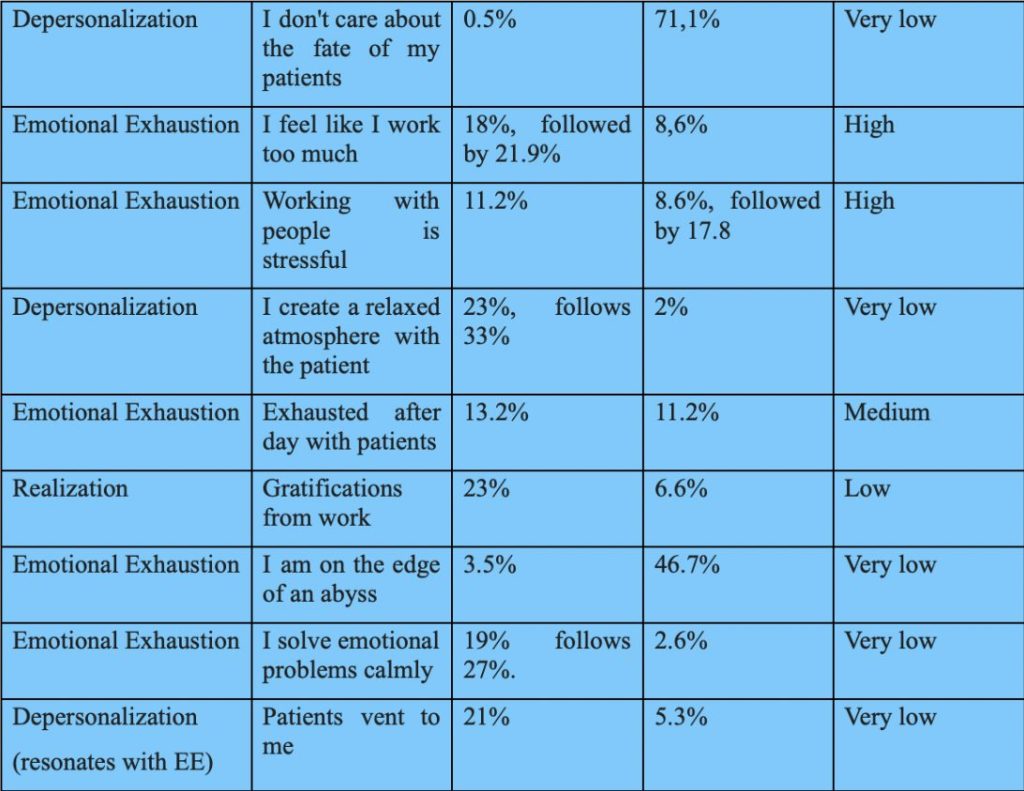

Here is a very summarizing and extremely polarized table of Maslach’s test: the questions with the always and never answers, the range and the burn out risk index: remember the three spheres of the test (Depersonalization, Emotional Exhaustion, and Realization)

Maslach’s test results

Here is a very summarizing and extremely polarized table of Maslach’s test: the questions with the always and never answers, the range and the burn out risk index: remember the three spheres of the test (Depersonalization, Emotional Exhaustion, and Realization)

These are the summary results of response bias. The indications are many, and certainly to be intersected with the narrative fragments. However, even in stand-alone mode they give us a compass of the possible burn out of healthcare in Italy.

Depersonalization, i.e., treating the patient as an object, cynicism, slow violence toward patients, absence of empathy, brutality from these responses is just a very remote hypothesis: on the contrary, the mission of care is “sacred, untouched,” patients are listened to, they can vent, they are welcomed with their emotions, logical plans for their care are thought of. And perhaps it is from talking with patients that the fundamental energy is created to move forward in the health care system by creating a Common Wellbeing between patients and health care professionals. On this front, the risk of burn out is not really infinitesimal. Even in the narratives of “I want to…” Patients are at the center:

- Continue to do the best I can do

- continue the collaboration as long as it is possible for the organization and reconcilable with my other commitments.

- I want to cure

- possibly be helpful

- continue to love this work

- To leave my know-how to the younger generation and my passion for my profession, which cannot be separated from the knowledge that a helping profession is CHOSEN and that it serves people

- Doing my best

- I would like to create a welcoming, creative, professionally stimulating climate. I would like skills to be evaluated for results achieved, also listening to patients’ opinions, I would like less bureaucracy. I just want to work doing what I studied for with passion

- I want to be there. And find the best way. It is not others who give us satisfaction. I find it in looks and gestures. And in the relationship not always positive but I look for it to be so. I want it to be such

- Continue this work, implementing aspects of information and support for families and training for health workers

- Continue to always do my best toward patients

Emotional Exhaustion almost never comes from related questions with patients, whose risk is low, but from the system, with fatigue, fatigue, energy required, which is no longer a human burden, but becomes inhuman. So even the concept of Compassion Fatigue, fatigue from too much compassion with patients is undermined, compassion paradoxically is energy, it motivates, it makes people give their best, it does not exhaust. Energy is undermined by routine, that “I feel tired in the morning,” which should instead be the time when we ask ourselves “how can we contribute with our work today?” Stress responses with colleagues (people) do not seem so polarized. On this front, the risk of burn out has been identified in workloads (I feel consumed by work), and this is where remedies need to be put in place immediately that go far beyond meeting daily budgets.

With respect to the narratives to the narrative invitation “I feel…” here are some verbatim underlining tiredness:

- Overwhelmed, exhausted, lifeless. Everything that used to give me pleasure in my work now weighs a ton on me. Whereas before I would stay extra hours if there was a need, now I can’t wait to get away

- …ethically challenged, aware of being limited in treatment options by bureaucratic practices and by medicine administered and not practiced according to true needs

- Constantly suffering from increasingly demanding workloads at high responsibility, demotion perpetrated due to chronic shortage of professional figures.

- Incomplete, with the many staff and material shortages. Overworked, given the profuse incompetence and/or unavailability of colleagues/staff

Fulfillment is apparently ambivalent in that it is composed of self-realization through the maturation of one’s skills, and the absence of recognition from others: many feel frustrated, not understood but they are the same ones who feel good, self-esteem, are full of gratification given by patients, and by their own increased knowledge. The risk of burn out, although no one is on the precipice, consists in the theme of frustration due to absence of gratitude from management (and not from patients and colleagues). Here are some written accounts that reveal to us this sense of Malaise-the narrative invitation was “I feel…” and Well-Being.

- Undervalued for acquired skills, personal qualities and resources, not involved in projects despite availability and titles

- Tired as if fighting windmills, underestimated most of the time especially when something needs to be changed, public health no longer puts the citizen’s health at the center so frustrated

- Underpaid for my professional skills. Underpaid for the responsibilities I assume. Little or no medical-legal protection. Frustrated for not seeing clear career possibilities.

- Often stifled by demands and things to do. I also feel useful when I can help people or colleagues in need. Lately I experience a sense of helplessness because of the difficulties of health care providers and the discomfort of patients in front of waiting lists.

- Fatigued, not valued not adequately paid

- Mobbed and pressured. Coordinated by people who do not understand (through ignorance and haughtiness) my role and my work

- Very well received, there is a familiar and smiling environment, a lot of personal autonomy and great appreciation for what everyone does and manages, without rivalry as was the case in the previous workplace I came from (university hospital company)

- Constantly unsure about my future and the possibility of professional growth. Unable to plan vacations or well-earned time off. Tired and exhausted. Happy with results and patients’ esteem. Helpful to patients. Esteemed by colleagues and patients.

- I have an experience of ambiguity, on the one hand I am happy because I am doing the work I like. On the other I feel misaligned with what the NHS is proposing today, the person is no longer at the center, there are economic and market interests. This is not the public health care that I helped to create

- Very good but very fatigued by accountability and pressure from regional institutions that demand data without assessing the quality of care delivered because they rely solely on checklists

The results of Maslach’s test on burn out, designed back in 1981, show how far health care professionals have come in embracing the need to be empathetic, compassionate without fretting, learning to embrace patients’ emotions and making it their strength, no longer their weakness: and this result at a time in history when the Italian projects we are aware of are called, for example, “Save the National Health Service.” The attitude of our participants makes us realize how much, once the willingness to profess care is embraced, it becomes an identity part of the person, epi-genetically transforming his or her DNA. The themes of caring, patient-centeredness, compassion, and inclusion are here on the table, and in great development in 2024.

The danger lies in the abuse of this caring profession by management systems, (not leadership), precisely because they are often “Good” people, even too “Good” people. People who do not know how to set limits and hurt themselves, not by the pains and illnesses they cure, but by the too many yeses by submission they say to higher hierarchical positions (some endowed with little reflection, and little natural intelligence). Submission comes at the expense of motivation, and this is an issue to watch for leadership to become wiser and more mature. And leadership that is absent and myopic and not serving puts the production of Common Good at risk.

Toward what policies?

I widen the topic and contemplate the issue of the medic*’s retirement at 72: it is a strategy due to the lack of existing health care planning since the days of big cuts in health care, excessive closed numbers at the faculty of medicine-(news on Jan. 23, 2024, maybe I will finally pass the Swiss and French model, whereby there will be no more closed numbers, but the value of students will be seen after the first exams to be passed) from unappealing contracts for doctors and almost “insulting” for nurses. Perhaps the politicians promoting retirement at age 72 do not know the fatigue of night guards, of frayed nerves in intensive care units, or of continuous contact with death in palliative care services.

Caring is a wonderful profession (and we understand this from how “happy” the caring professionals are with their patients) but there is also a necessary time for self-care: splendid the carers over seventy who responded to us, yet they are people who voluntarily “chose” to continue caring, they did not stay out of obligation. The truth is that “the King if not naked is scantily clad” in terms of system and resources. Now we need to make the health professions more loosely based, university paths less obsolete (full of notionism) and richer in training derived from the humanities. And broaden to young people, go out and gather them at high school open days, sending those doctors* and nurses* as witnesses who still believe in the mission to talk to them and explain the beauty of the act of care.

Merging the caring professions with biology, natural and social sciences, philosophy, and the arts right from college, (STEM disciplines with SHAPE disciplines) and throughout the time in the profession, so that it is a Life Long Learning that goes to fill the half-empty vessels energetically. But let there be no talk of cold and aloof health professionals: here, in the middle of this freezing winter, there is warmth with the patients, and lots and lots of feeling of the Common Good to be saved and protected: the demand, as we also read from the narrative part is to have recognition. It’s time for the top management to take the care to thank and say that its staff members/staff are worthwhile, to recognize and rebuild the interdependence of the teams, to find the economic resources to remunerate them/them adequately, and to motivate them/them through allowing people to take time for themselves, to rest without sucking them “into the tsunami waves.”