Narrative Medicine and Evidence-Based Medicine offer two distinct but highly complementary perspectives on healthcare. Each of them clears one of the two sides of the same coin: sides that practitioners are rarely trained to consider and manage together. Even today, most physicians, nurses, and other carers are almost entirely instructed on what is commonly referred to as Evidence-Based Medicine, even though some are beginning to consider this severely limits their professional reach. Disregard for the other side of care obstructs their understanding of the dynamics of meaning attribution in disease prevention, detection, and treatment. A small but growing number of healthcare professionals are aware of such themes, but very few seem to know how to leverage what Humanities and Narrative Medicine have been proposing in terms of theory and practice.

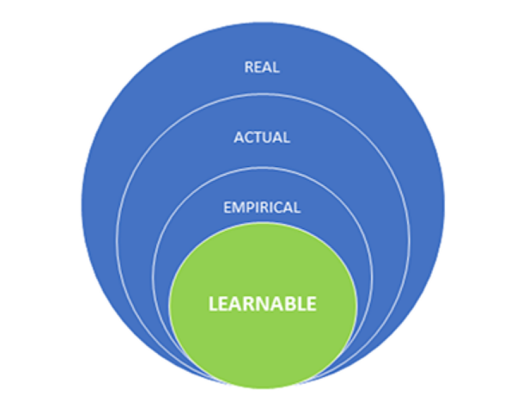

While professionally active in the fields of Adult Education and Healthcare for over 30 years, it is only in the last two decades that my efforts have focused on the study of meaning-making processes for individuals, groups, and organizations. It was at the University of Lancaster (UK) that I faced the ontological challenges deriving from the application of Bhaskar Critical Realist Ontology to Critical Discourse Analysis. There, I developed the Learnable Enhanced Bhaskarian Ontology – LEBO (Magni, 2011)1, which was recently revised and expanded in Magni, Marchetti, and Alharbi (2023)2. LEBO (see Fig. 1) follows Bhaskar’s original proposal to consider reality as an ontological dimension composed of causal forces that may or may not actualize in space and time and may or may not be/become empirically detectable. Furthermore, the Theory of Learnable emphasizes that not all – of what is Real, Actual, and Empirical – falls under the attentional radar of individuals/societies and/or can be elaborated by humans. The Learnable embodies and exposes the selectivity of human cognitive systems and it stresses the ontological and epistemological relevance of attentional neurolinguistic dynamics when it comes to studying human detection and elaboration of reality.

Fig. 1 Graphic representation of Learnable Enhanced Bhaskarian Ontology – LEBO.

LEBO assumes that language is more than just a tool for communication; it accounts for the coding and decoding system that affects our perception of reality and influences our decision-making processes, as it participates in the complex process of semiosis. Language enables us to conceptualize and express our thoughts, emotions, and experiences. It serves as a framework for organizing and interpreting information, and it has an impact on our understanding of the world around us. By recognizing language as a system of thought – that is, as a system sustaining and sustained by intra- and extra-cranial processes – healthcare professionals can gain a better understanding of what underpins patients’ and carers’ experiences and their behaviours.

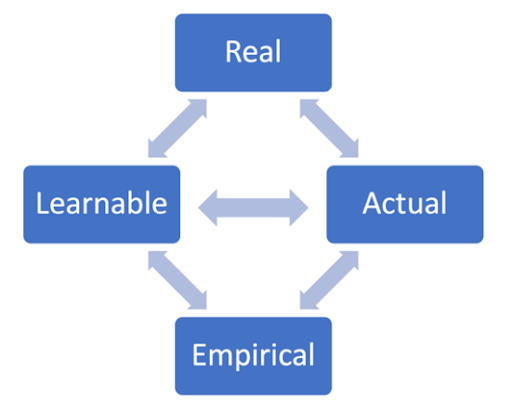

Bhaskarian ontology is frequently described as stratified and tripartite. By contrast, LEBO is quadripartite, and it introduces some other significant differences. While Bhaskar’s proposal appears to imply the existence of a diachronic and unidirectional linearity that connects the different strata of its ontology, relationships in LEBO quadripartite stratification can be synchronic, circular, and multidirectional (see Fig. 2). Such differences open the way to interesting epistemological reflections and applications, and they seem to respond to some of the most relevant critiques that Fairclough, Jessop, Sawyers3, and other scholars have repeatedly moved to Bhaskar’s ontology.

Fig. 2 Comparing Bhaskar’s and LEBO’s stratifications.

Here are some epistemological implications of the different stratification perspective introduced by LEBO. In the search for the causes of empirical events, a diachronic, unidirectional, and linear ontology directs the search for final explanations only towards actual space/time dependent forces (which appears to be relevant and sufficient for Evidence Based Medicine). On the other hand, because of its emphasis on synchronic, circular, and multidirectional relationships, LEBO effectively accommodates for the impact of multiple agents on any data observed: a flexibility that is now required by most sciences, including Real World Evidence Based Medicine.

While other texts4 provide a comprehensive account of studies pertaining to the aforementioned ontology, this article emphasizes the integrative power of LEBO and encourages readers to consider the role played by language, as a system of thought, in healthcare. In this regard, LEBO appears to represent an intriguing ontological framework because it specifically accounts for language as a system of thought: that is, LEBO encourages viewing language as a set of symbols that reflect, sustain, shape, and drive human thoughts rather than as a tool for communication. Language helps us conceptualize reality into words and/or strings of words, where stratifications of thoughts, emotions, and experiences converge. Conceptual metaphors and similes frequently condense our beliefs and serve as linguistic frameworks for capturing, organizing, and interpreting information, influencing our understanding of the world around us. Recognizing language and its impact on thoughts allows healthcare professionals to gain a better understanding of the cognitive processes that underpin both patients’ and their own decision-making and behaviours.

LEBO also assumes language as a key to performing deeper analyses and achieving broader interpretations of human symbolic representations, as it influences people in any context, including the world of care. Language is therefore proposed and used to detect and interpret the most relevant symbolic representations and to trace the roles of such representations in decision-making processes and behaviour prompting. Metaphors, similes, and other linguistic elements are more than just rhetorical devices; they have a significant impact on how people perceive and interpret information. Examining language and conceptual metaphors used in healthcare settings reveals beliefs, values, and cultural norms that underpin cure decisions and behaviours that patients, carers, and healthcare professionals are more likely to adopt. An understanding that is expected to inform more effective and personalized Real-World Evidence Based Care strategies and interventions.

Aside from the ontological and epistemological areas, where LEBO can bridge the gap between Evidence Based and Narrative Medicine, research in the field of Learnable Analysis also offers some very practical and operational guidance. This includes the proposal of an overall Learnable Analytical Approach and a set of linguistic clues that can be leveraged to highlight, within healthcare discourses and medicine narratives, the areas where subjectivity and cultural elements collide with the assumptions at the basis of Evidence Based Medicine. A collision that jeopardizes feasibility, effectiveness, and/or efficiency of cure protocols that have been built around population-level evidence, rather than individual-level care and its requirements.

In a nutshell, the Learnable Analytical Approach emphasises the priming and attentional effects of Lexicon, Grammar, and Syntax on the decision making and/or behaviours of individuals and communities of practise, and thus on patients, carers, and healthcare professionals in general.

- In Lexicon, Learnable Based Linguistics highlights the link among sensorimotor experiences, affordances, at the basis of concepts and their representation in the meaning of words.

- In Grammar, Learnable Based Linguistics highlights the differences in the attentional function of nouns, adjectives, verbs, adverbs, and other operators.

- In Syntax, Learnable Based Linguistics highlights how the ordering of words guides people attention onto the different representational elements within words strings and set tracks/scripts for the elaboration of the concepts with impact on decision making and/or behaviours.

Let’s take Covid-19 as an example of how Learnable Analysis can be used to identify the intersubjective symbolic path – i.e., the medical learnable – along which healthcare discourses appear to have developed during the pandemic. A symbolic path can be traced by some key lexical, grammatical, and syntactical choices that characterized the narratives used at various stages of the pandemic event and its evolution. Indeed, the pandemic provided numerous examples of how linguistic choices can frame healthcare narratives, subsequently directing some key decisions and actions of patients, doctors, and other key players in the healthcare ecosystem.

At the lexical level, some discrepancies and discontinuities in the semantic field emerged, characterising one of the most frequently used words in that context: the noun vaccine registered a significant change of meaning, as the affordance most relevant in determining its meaning shifted from injectable substance preventing contagion to injectable substance minimising the effects of contagion. No neologism was created to illustrate this peculiarity and substitute the term “vaccine”. On the contrary, the same noun was constantly used, potentially expanding beyond any reasonable limit the advantages that some vaccines, despite their reduced efficacy, could continue to enjoy: benefits ranging from preferential processes in registration and public financing/advertising of vaccination campaigns.

At the Grammar level, the call to action first emerged with the frequent leveraging of nouns-to-verbs transformations (i.e., distance => to distance; quarantine => to quarantine), then the priority of such actions was reinforced with the nominalization of verbs (i.e., distance => distancing, quarantine => quarantining) in the numerous discourses and narratives pertaining to the pandemic. Finally, to protect the community from the expected phantoms/fears (i.e., the disruptive social effects of distancing), the linguistic exorcism5 of “social distancing” (i.e., with the adjective social semantically contrasting the nominalized verb distancing) was preached.

At the Syntactical level, “Covid-19 is like the plague in the 16th century” is the prepositional metaphor 6 where the aforementioned learnable linguistic discrepancies converged. This metaphor effectively classified Covid-19 as one of the deadly diseases and may have contributed to the postponement of efforts to find a cure by focusing resources and attention on anti-contagious measures such as masks, quarantines, social distancing, and vaccinations.

Indeed, diseases and healing events can be studied as existential discontinuities that are captured and elaborated by the human symbolic function as signs requiring some form of meaning attribution. In the absence of specific guidance from healthcare professionals, these discontinuities ignite a search within the semantic repertoires available to the communities to which each affected individual belongs and/or identifies with. Unfortunately, such semantic repertoires may or may not serve the healing purpose, and in some circumstances, they may even corrupt the assessments/decisions of healthcare professionals. Language plays a crucial role in these processes as it allows people to make sense of their experiences, express their emotions, and communicate their needs. Language also reflects some of the most significant discontinuities that people face and occasionally even serves as their source/reinforcement. This is why I strongly encourage the adoption of narrative medicine and the humanistic perspective in healthcare and in the training of healthcare professionals. These approaches offer the opportunity to bridge the material and immaterial elements involved in the management of diseases and facilitate healthcare professionals in managing the linguistic and existential discontinuities they may encounter.

In summary, there is mounting clinical evidence to suggest that patient outcomes and experiences are enhanced by more meaningful and individualised care. This is encouraging a greater level of integration of data and insights derived from patient and carer narratives into the curricula and practises of healthcare professionals. The integration of Evidence-Based Medicine and Narrative Medicine in medical education and daily practise continues to face numerous challenges, some of which are philosophical in nature, and LEBO appears to address them by providing a solid epistemological foundation for both Evidence-Based Medicine and Narrative Medicine.

In addition to bridging the epistemological gap between traditional medical perspectives and humanities, LEBO opens the door for the use of language analytics in the study of the complex dynamics of meaning attribution, the decision-making process related to treatments, and the behaviours and practises of care, in various healthcare settings.

In this short text, I hope to have sufficiently illustrated not only the theoretical, but also the practical contributions that Learnable Theory and Analysis can make by concentrating on the impact of language-driven attentional processes in healthcare discourses and practises. With that in mind, I encourage healthcare professionals to learn more about the resources that Humanities and Narrative Medicine offer to recognise and address the most intimate perspectives and beliefs that affect patients, carers, and other stakeholders in their relationships with healthcare and wellbeing. To facilitate and achieve all of this, I invite readers to recognise the importance of language as a thought system and hone the skills required to quickly identify, examine, and resolve the discontinuities that can be detected and addressed in narratives and discourses. The time has come to move beyond Evidence-Based Medicine and respond to the call for a more comprehensive perspective. Real-World Data, including patient and carer narratives, appear to be necessary enablers for personalised medicine, individualised care interventions, and value-based procurement: the three key ingredients for higher levels of efficacy, efficiency, and satisfaction across the entire healthcare ecosystem.

Notes

(1) Magni, L. (2011). Research proposal for the application of critical discourse analysis to the study of learning cultures. Journal of Critical Realism, 10(4), 527-542.

(2) Magni, L., Marchetti, G., & Alharbi, A. (2023). Learnable Theory & Analysis. Luiss University Press, Rome.

(3) Fairclough, Norman, Bob Jessop, and Andrew Sayer. “Critical realism and semiosis.” Alethia 5.1 (2002): 2-10.

(4) Magni, Luca. “Research proposal for the application of critical discourse analysis to the study of learning cultures.” Journal of Critical Realism 10.4 (2011): 527-542. Magni, L., Marchetti, G., & Alharbi, A. (2023). Learnable Theory & Analysis. Luiss University Press, Rome. Magni, L., Marchetti, G., & Alharbi, A. (under publication). Learnable based Linguistics for Business Leaders. Luiss University Press, Rome.

(5) Linguistic exorcisms are defined in Magni, Marchetti and Alharbi (under publication) as the coupling of a noun and an adjective, that do not belong to congruent semantic fields and together aspire/pretend to neutralize/subjugate incumbent risks and evils – e.g. Vertical Forest, Ethical Products, etc.

(6) Definition and analysis of prepositional metaphors, as well as their relevance as bridges between language, decision making and behaviors, can be found in Magni, Marchetti and Alharbi 2023.