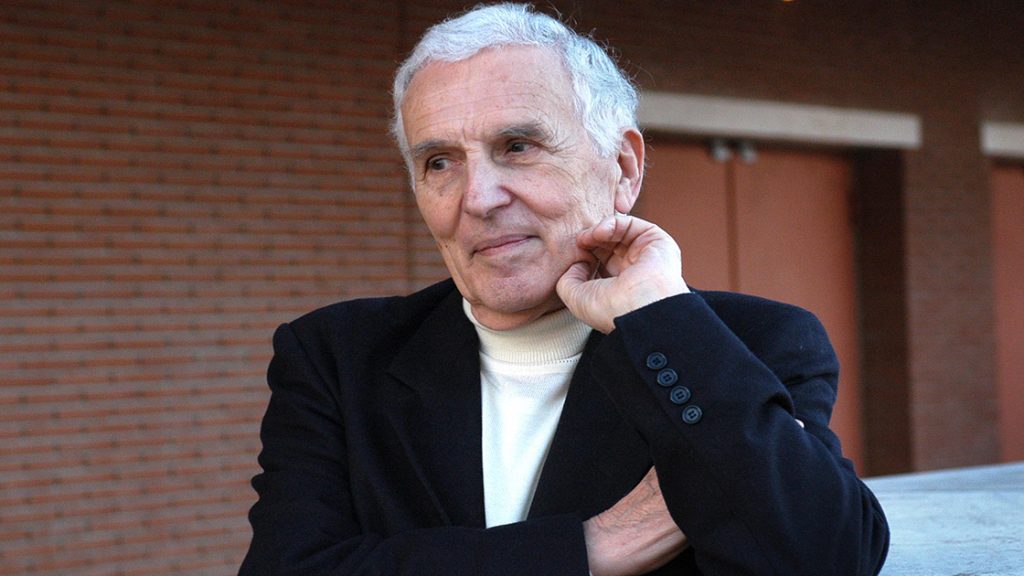

Silvio Angelo Garattini is an Italian oncologist, pharmacologist and researcher, president and founder of the ‘Mario Negri’ Institute for Pharmacological Research.

The conversation with Professor Garattini is always stimulating and educational: we talked about language, a topic I addressed in the first chapter of the book Health humanities for quality of care in times of Covid-19 published by Springer. The WHO bulletin of 11 March 2020 announced the pandemic, with a communiqué, which Professor Garattini comments, unfortunately arrived late, but with the right words: ‘We have never before seen a pandemic sparked by a coronavirus. This is the first pandemic caused by a coronavirus’: we are facing a new pandemic never seen before, the child of globalisation. The professor adds that it is not possible to make analogies with the Spanish flu, the pandemic that developed at the end of the First World War or other pandemics in history. This one is new, the only child of our times.

In the COVD-19 pandemic, what was new, apart from the speed of contagion due to constant travel, was that it undermined the achievements and advances of modern science. There has been a lack of humility on the part of the scientific class in admitting uncertainty in the face of the unknown, and declarations of pseudo-certainty have been made on unknown ground. In the first chapter of the book Health humanities for quality of care in times of Covid-19 I tell of extraordinary collaborations between scientists as never seen before 2020, of the possibility of publishing and reading every possible scientific article free of charge, and here the professor sees further: ‘yes many collaborations, but spontaneous and not organised: how many opportunities have been lost to set up controlled clinical studies, and I am not just referring to vaccines but to all the pharmacology that was used when vaccines did not yet exist. And in addition, there was a lack of European and Italian direction in collecting information on the sequelae of covid-19, each clinician wrote their own data and published them thinking they were contributing to scientific growth but in reality they were collected in profoundly different formats and therefore not usable for meta-analysis’. The communication to the public has been patchy: citizens accustomed to the ‘health at all costs’ model, spoilt by the market, have not tolerated the uncertainties and the constant changes of opinion of scientists. It was more honest to say that they were navigating by sight through a single Ministry spokesman. And on the subject of uncertainty, Professor Garattini refutes another cliché, the one we have used in the historicisation of wars and pandemics, the living with uncertainty: ‘I was there during the Second World War, I was twelve years old and I did not feel, nor did we feel the uncertainty and precariousness of life, I went to school regularly, back then we were starving’. My comment is that we now live in the Liquid Society described by Bauman, the consumerist society as Marcuse predicted in his One Dimensional Man “that of the all at once now-consumption”, and therefore any situation that is not quickly turned out generates uncertainty and intolerance.

That is why we feel such a strong fear of uncertainty, hoping that everything will return to a safe normality, which cannot exist even in science as a safe haven that deals with probabilities and not certainties, as Popper’s falsification principle states.

I could not resist and asked the Professor about vaccines, about which in the book I mainly deal with the choices of social inequality in the vaccinated population, which happened in early 2021. Professor Garattini expressed himself clearly, the virus has changed in its essence compared to that of 2020, it is more contagious, it resists summer temperatures and is perhaps less lethal, but not everyone is to be vaccinated, only the most fragile categories, and not necessarily all the elderly because one has to understand what the objective physical state of health of a 50-year-old and an 80-year-old is, beyond mere age classifications.

In the book Health humanities for Quality of care in covid 19 times a chapter written by Paola Chesi is dedicated to health professionals in the path of the pandemic: at the time they were considered ‘heroes’, today they are devalued and criticised in a system considered malfunctioning.

What can be done for them? The professor tells us that not all health professionals really experienced the Covid-19 camp during the first wave, several were in the rear: but it is important to broaden the Horizon and talk about the System. In his book The future of our health (Edizioni San Paolo), the professor dreams of a reform of the health service which, he reminds us, is an intangible common good, and which is unfortunately undervalued and taken for granted: he tells me about his father who had to work double jobs, day and night, to pay the medical bills of a sick family member – in short, what happens every day in the United States, although the TV series tell us about an extraordinary health service with excellent surgeries, willing to treat the rich and socially fragile as in the TV series The Good Doctor.

Let us go back to Italy: the public health service must be saved and preserved with its professionals; first of all it is we citizens who are called upon, not only with our rights but also with our duties. Taking care of ourselves through correct lifestyles (prevention) and this is how we can already prevent 60 per cent of chronic diseases: no smoking, no alcohol, good nutrition, sport and, I would add, sleep, and the professor informs me that the brain produces so much waste during the day that only during sleep can be disposed of. Thus, prevention starts with our responsibility, and we would have far fewer surgeries full of patients with chronic diseases. Then, and I also add my voice to the authoritative one of the Professor, a health care free in its choices from government policy, with independent technical-scientific institutions, and added free from the sluggishness of public administration. “I would like to see intramoenia abolished so as not to see such long waiting lists for patients; I would like to see higher salaries for doctors and nurses, I would like to see less flight of doctors and nurses – already very scarce – abroad for higher salaries.

I ask about the possible abolition of the numerus clausus at medical universities; ‘we would see the effects in ten years’, and in any case I welcome the evaluation of students’ merits after one year as happens in France and Switzerland, universities without a numerus clausus. But the real problem is that Italian academies are not equipped for this, they are small. He proposes the reorganisation of hospitals: fewer structures but with better and greater productivity, then general medicine must be reorganised by uniting family doctors with nurses on the territory and the social; social assistants to deal with bureaucratic issues, ensure help for the elderly, in short, social-health paths. He advocates greater use of telemedicine to listen to patients, – interesting what the professor says: ‘patients need continuity to be listened to, not to be left alone’, that is the main use of digital healthcare.

And then in terms of cultural impulses, the need for scientific thinking must be divorced from political thinking and the too much pressure of the wild market. It is from school that one learns to ‘reason and think’ in a scientific way: the professor is provocative ‘there is too much room for the arts and literature and not enough for the sciences in Italy’, here I propose that even the teaching of physics can be done with the arts to create, in terms of languages, a more fascinating and engaging way for children and young people. Let us agree with the professor and find the mediating ground: the scientific world and the humanistic world must be integrated harmoniously, and not the disciplines placed at the expense of each other. Continuing to talk about young people, I come to the last chapter of the book Health humanities for quality of care in times of covid 19, there is a personal tribute from me to the young people who by respecting the lock down have saved our lives and thanks to the perhaps too prolonged maintenance of distance learning. “Yes, we should thank them and we will discover in a few years the damage of this forced isolation at an age when the brain is still developing and has the greatest need for social interaction.” We have not thanked them enough.

As usual, I come out of this conversation enriched, dreaming of a competent healthcare system, meritocratic in the most honest sense of the word, living peacefully with the uncertainty of today and tomorrow.