Multiple Sclerosis is a chronic-progressive neurological disease that has a severe impact on the quality of life of the individual and the whole family from the moment of diagnosis. The aim of our work was to try to identify the communication methods to be preferred and those to be avoided in order to limit as much as possible the trauma of the discovery of the disease.

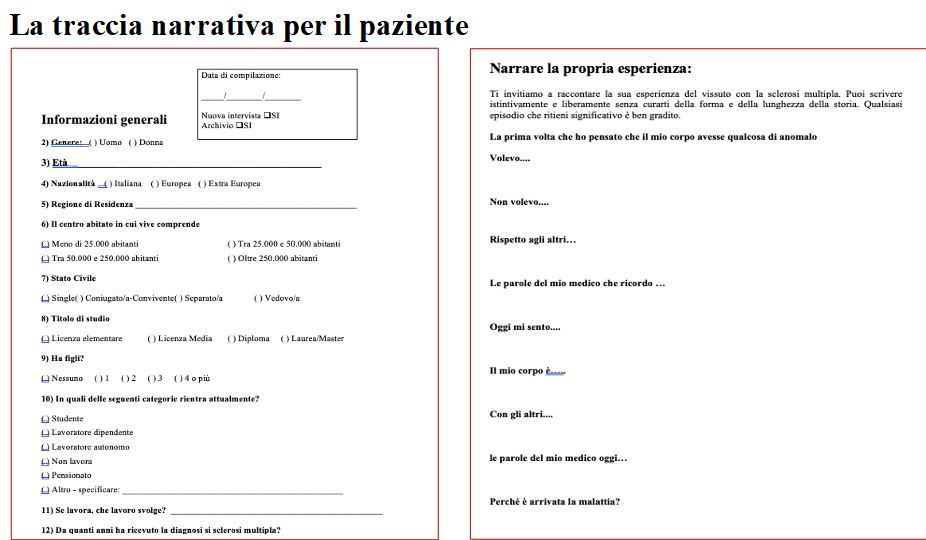

To this end, the narratives (45 in total) of people with MS (average age 42 years, 35% male, 50% married) and their care-givers (48 years, 36% male, family members living together) were collected. The narrative followed a predefined, but extremely free track. The stories refer to the communication of the diagnosis, in three different groups: people diagnosed within the first year, within five and after more than ten years.

The ‘right words’ of the doctor are something much more ‘real’ in the treatment pathway than one might think: verba non volant sed manent! A person may remember superficiality, indifference, coldness even for decades, despite a positive experience of coping with the disease.

According to Launer’s classifications, more than half of the patients’ narratives are progressive, although in the narratives linked to progressive forms of illness, terms or metaphors that refer to concepts such as nightmare, chasm and words such as anguish, fear, death emerge more frequently. Caregivers’ narratives follow the same proportions between progression and stability: female partners seem to suffer more from the burden of care, generating stable type narratives.

The need to find the “right” words in the doctor-patient relationship prompted the need to interview patients who were in the medical profession. The doctors/patients worked and partly work in surgical branches and this stigmatises their efficiency profile in caring for others. The doctors/patients all had to modulate, if not suspend, their surgical activity, leading to a feeling of futility which, in the most serious cases, was not compensated for by other rewards. The relationship of the doctors/patients with their caregivers was inconstant. Each one of them reported to have “understood before” the examinations that he was suffering from MS: “I went to the hospital pointing out that it was that pathology”, “I had understood it before the magnetic resonance, my radiologist uncle confirmed it to me, he didn’t say anything, he nodded, crying, to my question”.

The doctor-patient/doctors relationship places one in front of a mirror. Looking at each other brings up conflicting emotions and this conflict appears clearly in the narration: “I didn’t want to do the lumbar puncture, my doctor got angry”, “I would like to be treated as I treat others”, “I denounced my colleagues because they didn’t give me the therapy”, “my doctor is lovely, I like the frankness”. The internal split between caring and needing care is projected onto the carer, who becomes both accomplice and enemy. The reflection of the new I, more or less prostrated by the pathology, does not coincide with the image of efficiency and solidity that should appear in the mirror.

The greatest conflict that three out of four of those interviewed complain about is not being able to practise medicine as they did before their illness: ‘I’ve shut myself off. Judgment from others is inevitable, it bothers me! I have never judged my patients”, “I am not effective and efficient!”, “I was aggressive, very attentive and a hard worker. After the diagnosis my head physician fired me and my colleagues disappeared. They didn’t care”. Finally, the loss of work capacity meant that there was no planning: ‘I can’t plan, it’s pointless’, ‘the lack of autonomy is very serious’.

The last provocation of the narrative exoskeleton was “why did the illness come”. All the interviewees concluded that MS ‘arrived’ after a strong period of stress, whether personal or professional, excessive workloads, unrewarded recognition, fatigue in learning and caring for others. MS has, like all autoimmune diseases, an inescapable link with stress. Chronic exposure to cortisol induces alterations in the immune response in predisposed individuals.

The silence that preceded the interviewees’ response poses the question to the treating physician about how exciting, but also tiring and disturbing, it is to carry out a health profession, and imposes the need for humanistic support to the operators. The awareness that in order to treat others it is necessary to maintain a zone of protection of one’s own well-being is essential to protect the doctor himself.

Reacting to the disease is strongly linked to an empathic and trusting relationship with the clinicians, as C. tells us: “today we have found a doctor who is very willing and ready to listen to every new disturbance that the disease presents. The greatest good fortune in this condition is the awareness that there is someone ready to help and in some cases to calm down when there is something wrong”, as well as the ability to draw on personal resources and a serene process of acceptance of the disease, as Z. states: “the secret is not to think about oneself more than one should, it is important to understand how I can deal with it, not why it came”.

For everyone, the cure pathway is inner rather than outer and does not begin or end with an illness: leaving or ignoring unresolved existential problems is the worst substrate on which to live and on which pathologies can graft, which can also be the final manifestation, as S. expresses it well: “being forced to be strong in the way others wanted, before the body gets sick and the soul screams”.