The etymology of the word Europa is uncertain, perhaps it derives from the ancient Phoenician, ereb (west), but the phoneme eu at the beginning of the word transports us to imagine something good and positive.

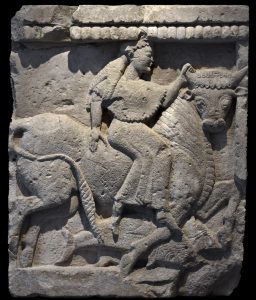

In Greek mythology Europa’s parentage is uncertain: Hesiod wants her to be the daughter of Thetis and Oceanus, in the Iliad she is called daughter of Phoenician, while for Herodotus she was princess of Tyre and daughter of its king Ageron. Whatever her family name, the myth tells that one day Europa was playing on the beach when she was noticed by Zeus who fell in love with her. In order to get the girl, Zeus asked Hermes to move a herd on the beach and, taking the form of a white bull, he broke into the cattle and approached. Europa surprised by the animal’s meekness, when it crouched beside her, she climbed onto its back. Thus Zeus was able to abduct the maiden by galloping towards the sea, which he crossed, still in the form of a bull, to reach the island of Crete, where perhaps by some other expedient he defeated the girl’s resistance. Thus were born the three sons of Europa, Minos, future king of Knossos, Radamantes, later a judge in the afterlife, and Sarpedon, a strong ally of Troy. Before leaving Europa, Zeus gave her three gifts: a faithful dog, a bronze colossus to protect Crete and an infallible javelin. Europa would then marry the king of Crete, Asterio. Meanwhile, Europa’s brothers toiled in the search for their sister, never finding her, but founding numerous other colonies in the Mediterranean.

In Greek historiography, the name Europa denoted the part of Thrace below the Balkans, then for the Latins the whole region. As the opposition between West and East built and consolidated, Europe and Asia came to be defined as two strong but hard-to-define entities, one characterised by a spirit of freedom, the other by despotism. This is a Western rhetoric that cyclically resurfaces, of which there is little awareness.

The years immediately following the Second World War led to an intense reflection on what it means to be European. Protagonists of this period were Curtius, Warburg, Auerbach, Spitzer. Their reflection brought out even more clearly than before how much the question touches memory, history, the construction of an idea of Europe (cf. Chabod, Storia dell’idea d’Europa).

In short, Europe is an idea, an ideal, or perhaps even better, a set of values, starting with that of welcome. Europa in the myth was a foreigner who, kidnapped, found refuge on the island that was to be the cradle of European civilisation. Europa was then a flag of freedom and after the Second World War rebuilt itself on the foundations of a collective memory. Its history, which is also ours, is a narrative of hybridisation, mixing and reflection.

It is precisely this plurality and depth that distinguishes the European Narrative Medicine Society.

Please leave us a word for your feeling of Europe.

Duke patur parasysh se Evropa ishte nje vajze “Robine” robëreshë, dhe ashtu sic kemi te ditur se Evropa i perket Henes se Jupiterit atehere une mendoj se kemi prej gjuhes shqipe: EV+ROB = EVROPA, ku Ev = Eva dhe Rob = robëreshë