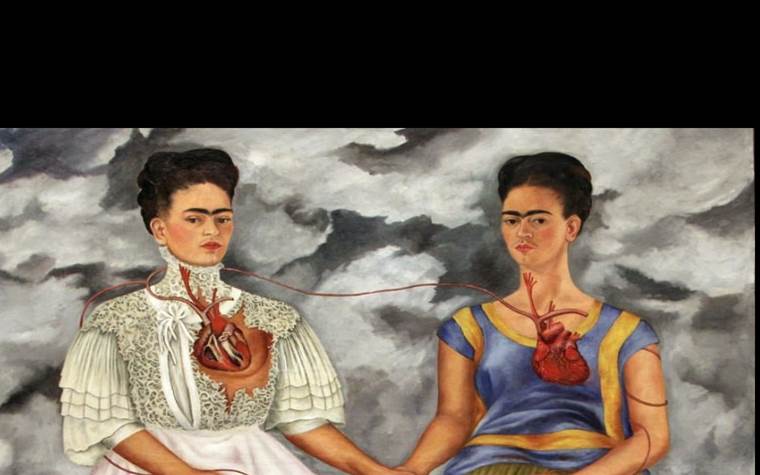

Since 2015, the Privacy Commissioner has approved the fact that in Italy citizens can consent or deny or not express about the donation of one’s organs in case of death upon the necessary attainment or renewal of one’s identity card in the municipality. And it is a source of Common Good, of altruism, a sign of a civilized society to move in this direction, having in mind no longer just oneself but knowing that one is still useful after one’s life. Some people consider one’s organ donation as continuing to survive in another body: as studied since the days of the first transplants,[1] the theme of subjectivity in the person who receives the dead donor’s organ becomes vivid, thinking of acquiring not only the organ (in a metaphor, where body is machine, the new organ becomes the spare part), but also the donor’s emotions, tastes and attitudes.

Through a review of social science research conducted with organ transplant recipients, it is shown that the most frequently mentioned identity changes are an alteration in gender or age, or preferences for food or music. The medical and social science communities have long sought to offer explanations for these stories, which relate to social theories of contagion and contamination and biological explanations for the existence of cellular memory.

Gillian Haddow of the University of Edinburgh writes: Biomedical practices and advances in transplantation are testing the limits of the Cartesian model of separation and duality (body- res extensa, a machine, and soul- res cogitans). More recently, research conducted by Margrit Shildrick of Warwick Univerity[2] suggests that very few of the 30 heart transplant recipients were able to see the heart as a “transferable, disembodied organ that shed all vestiges of its previous location…aware that their sutured bodies spoke of a different way of being-in-the-world.”

Referring to a “reverse childbirth” analogy, Margrit Shildrick and her colleagues suggest that just as a pregnant woman needs to acclimate to being pregnant and living with an additional self in the form of a growing child, similarly organ transplant recipients need time to feel comfortable with a foreign addition, in this case an organ and not a child. Research suggests that almost all recipients suffered a general sense of discomfort after heart transplantation and that recipients are challenged by the “persistence of the other” and the “cultural baggage” associated with the heart, seen as the biological and metaphorical center of life. In this conception, organs “are always more than just things.”

We move away, from the perspective of narrative medicine, from Disease, the reductionist biomedical model, and Restitution (e.g., I undergo the surgery and you give me back a functioning heart) to enter the world of Illness and Quest, with the open questions of subjectivity, “Who was the donor? How did he/she live? How will I live with his/her “being inside me? How will I adapt to the strangeness that has entered inside my body? What gratitude will I be capable of?” — and again. endless other questions.

Returning to the ‘transplant consent and identity card’ operation, for the sake of convenience, citizens have been involved at the registry office on the post-mortem choice of transplant, just when they are getting the certificate of their identity, without knowing what possible existential questions both donating the organ and receiving it raises. And it is only the narrative that will give meaning to the choice of gift and reception.

Having painted this general picture, I descend into the personal anecdotal and recount a very recent episode that influenced my choice to deal with transplant and end-of-life narratives. On January 27of this year, my wallet was stolen, containing among other documents my identity card: I made an appointment at the town hall, and the first available time was April 5, 2024.

On Friday morning, April 5, I go to the municipality on time, where they give me a waiting code: I sit and wait, with my photo in my hand and the carabinieri’s report: my number comes up and I approach the counter where the person who is to prepare my new card is standing. She doesn’t look up as I arrive and say ‘good morning’ and she doesn’t answer and continues to chew a breadstick. She has a package of snacks there with her. I slide the police’s report and the photo under the counter glass, but alas nothing, she eats undaunted: she looks at the PC video starts to enter my name, then asks me “how tall are you,” I answer her, for the first time she looks up at me: she offers me a breadstick.

It is done, I think, we have found the “connection”, ‘Address?’ ‘Put your finger there for the imprint,’ falls the on line of the municipality, obsolete technologies, everything to be redone, name, height, residence, imprint. And then suddenly she asks as she pulled a new breadstick out of the package to bite into it, ‘Are you for, against, or not for organ removal after death? ‘, there and then I go into survival mode “attack or flight”, “I do not express myself” … then I ask her – and here my ignorance comes out – but at the last renewal of my identity card in 2018 they had not asked me my opinion about this topic- “why this question?”, she avoids the look, “Nothing, it is a survey wanted together with the Ministry of Health to know the opinions of citizens”. Mind you, opinions, not wills: then I ask her to change my answer and write ‘in favour’.

The technology crashes again, we decide on the delivery of my identity card, I pull out my ATM card to pay, strange it works. We arrive at the final moment of the signature; I have to check every piece of information, name, age, height, domicile, and on the fourth sheet I see it written that I have to sign that after my death I am in favour of organ transplantation. I sign anyway: it is not a subscription of an opinion but of a will, which I will be able to change (it is written as an afterword).

I walk out of the municipality stunned and feeling ignorant: I have been involved in healthcare for more than thirty years and I had missed this practice on the way. But then I think about the surreal conversation, the mystification of a will passed off as a survey, together with all the verbal and non-verbal erroneous possible perfectly apt in a dialogue between user and service. And I think that such a delicate request operation could be requested by the general practitioner and then sent to the Ministry of Health: and I think there should be a dedicated space for reflection, especially for young people whose organs are generally much more functional than mine.

How do you ascertain death? When does the explanation take place? I think of people in an irreversible coma – in a vegetative state – in short, a world of ethical questions opens up. The lady in the municipality was not ‘up to it’, though she kept asking the heights of others, for such an intimate and delicate question that is not a mere formality: but that is not her limitation, no one had given her proper training, and perhaps no one had wanted to see in depth what it means to have an identity and to give a piece of one’s identity to another. The recipients – ‘recipients’ in English sounds depersonalizing, the recipients, thanks to the pairing of identity cards and voluntary consent to explant will be able to go on living, and this is a precious commodity.

Along with social identity, so too is the identity of the body we inhabit and who we have been given. After that, all that remains is the name for a few decades, it is assumed that the memory of the name and the family history will stay for three generations: the body is soon dismembered, the height is lost, the domicile will pass to others, perhaps from this nation, perhaps from outside.

And so, despite the clumsy ways of some municipal employees and the path that might involve the person who by law protects our health, the general practitioner, we welcome the donation of even our own identity marked in our cells of our organs to help, if only in the short present of our lives, others, who are much more than pots (recipents) to be filled.

[1] Embodiment and everyday cyborgs: Technologies that alter subjectivity. Haddow G. Manchester (UK): Manchester University Press; 2021.

[2] Shildrick, M. 2015. Staying Alive: Affect, Identity and Anxiety in Organ Transplantation. Body & Society, 21, 20–41.